if you were around here this time last year, you might remember that i had an essay on La Chimera that i eventually pulled, as i was under the impression it was going to be published in a magazine….well that place shuttered (rip </3) and then i brought it somewhere else before i got scared and now it’s back to languishing in my laptop .. so i thought i would give it back to everyone! i’d like to think it’s a lot better than the initial version i put up here. this time, i’ve also done quite a bit of research and rigorous editing, so i hope you’ll consider supporting this publication.. :-) it does make a difference in getting the word out about my work + supports my ability to keep writing!

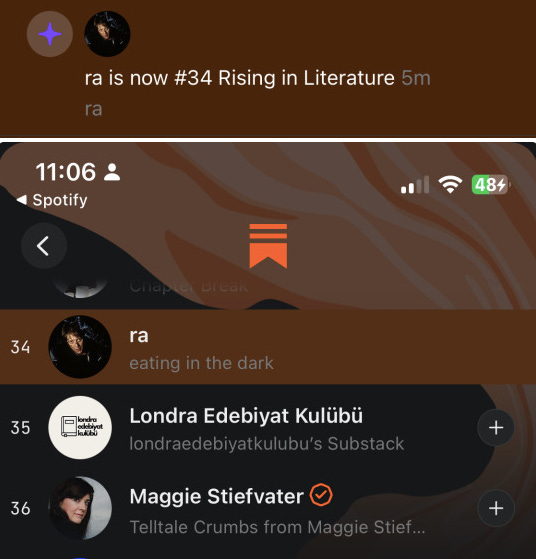

speaking of making a difference, last night i was informed that this publication (!) is #34 rising in the Literature category, a list comprised of greats like Marlowe Granados and George Saunders…

… so thank you so much for reading and supporting my work! none of this would really mean anything without readers, so thank you. on to the essay!

‘By the roots of my hair some god got hold of me.’

– The Hanging Man, Sylvia Plath

The year i turned twenty i spent six months sleeping with a tarot card under my pillow. i was told to do it during new moons, when i could feel the thinness of the veil and the hollowed-out sky, both of which were meant to facilitate some great looming sense of pressing your palm against the gauzy curtain which separates this world from the next, as if god were only a child half-heartedly playing hide-and-seek, wanting to be found. But i was turning a corner in age and desperate to be moulded into anything other than what i was, so i did it.

i picked The Hanged Man because his disposition resided somewhere so far beyond my imagination, it was a place i could not go. The other cards proved too familiar, and in this recognition i’d decided they were already ruined for having the audacity to reflect myself back at me. If i was going to drag myself around the hairpin turn by the roots of my hair, i was going to do it properly, until it left my scalp stinging. For weeks i scoured tarot books, all of which insisted that the power of The Hanged Man is in that he dangles there sacrificially, of his own free will. This was my trepidation about him, his willingness to surrender. He wasn’t hanging there because it was painful, because it was punishment, or because the rush of blood to the head made him dizzy enough to soften the edge of everything. He does it because he wanted to, and he could. i couldn’t figure out how to allow that. At that point, i was surrounded by deflated pillows and a collection of empty bottles under my bed, ugly and red-rimmed with the dried-up dregs of wine and flaked lipstick. Self-punishment is nineteen different kinds of boring now, but it was enough at the time to let me feel like i was kicking and screaming against everything. i’d balk at passivity, but free will was too painful to fathom.

It wasn’t lost on me that the Hanged Man also precedes the arrival of Death on his pale horse, the thirteenth card in the Major Arcana and a symbol of relentless rebirth, in which everything must go if only to make room for the unknown. This felt like giving something of myself away, i cringed at the significance. It was embarrassing to admit i actually wanted to be alive in a real way, or that i believed there would be enough left of my life to do this. The Hanged Man’s tranquil face gave none of this away, but i imagined he was less than impressed with all of my fickle fears. Who was i to believe he didn’t have his own feelings about being strung up there? Being wrenched from life as you know it and suspended upside down probably gives you lots of time to think, and i didn’t have anything to lose from trying, for once in my life. The Hanged Man knows this. His saintly circumference grazes hell, while his foot brushes heaven.

The next time i saw The Hanged Man, he arrived in the form of Arthur, who dangles upside down by a red thread looped around his ankle on the poster for La Chimera. i didn’t know to expect it when i walked into the theatre, so seeing him that way felt like walking through my own ghost. Unlike myself, Arthur is suspended in grief caused by the absence of his lover, Beniamina. He spends his life roaming in the wake of her, wading through the ruins and waiting to be taken by the sense of something beyond his earthly realm, to finally be able to feel her just as he remembers her. These searching feelings arrive as half-formed impulses towards the unknown, called ‘chimeras’ in the film, which descend upon him and turn his world upside down. Overcome by mystical revelations, this movement is reflected in that of the camera, which commences a slow, dizzying rotation, until it comes to rest on the figure of Arthur, now reversed to appear suspended in the dirt below.

To move towards closure seems out of the question, as he continually chooses to occupy the spaces of these ruined, half-remembered things that he then saves and keeps. His home – a cold, shabby hut secluded from the main part of town, where life seems to impose almost too painfully – teems with rescued objects restored to function, enacting his refusal to pit death against life. Arthur weaves the threads of loss and death into his way of living, with one foot in the grave at all times, as if holding himself in that precarity might finally force a revelation and return him to what he loves. His penchant for ruins then shapes our entire experience of the film, as its corpus is strewn with the fragments of a buried history which only he can keep, protectively enforcing his solitude as if to hear the chimeras better. Interestingly, Arthur is also the only English character in the film, making his collector’s approach to these deathly objects a significant character decision, as it calls on the picturesque tradition expressed across English landscape painting, which was informed by the Grand Tours embarked upon by young, wealthy Englishmen in the 18th and 19th centuries. One can imagine these young men at the beginning of their lives, staring endlessly into the sublime decay of the ancients as they travelled across Greece and Italy, or finding themselves strangely enamoured by a slant of light cast across a statue’s broken face, which roused enough sensation to be remembered only for what it affirmed about his own life. Namely, that it continued where others did not. In her essay on contemporary ruinophilia, Svetlana Boym underscores the affective impact of placing ruins in proximity with the human body as early as the 16th century, and asserts that this association and overlap has aided in creating a representative vocabulary through which the magnitude of the ruins gives our own aging, useless bodies some gravity. As a result, Arthur’s nostalgia for his lost love is tied irreparably to how it is represented by and related to the ruins.

Across the film, it’s a proximity to the ruins that creates meaning for its characters. It helps Arthur’s love for Beniamina to continue to mean something, in the same way that it helps his tombaroli (grave-robbing) companions feel that they are doing something to be remembered for. Even if that, in reality, amounts to nothing more than being chewed up by a system of capital premised on the relentless commodification enacted by museums, which decide to simply sell history to the highest bidder. In the face of this, it’s impossible for any of these endeavours to really mean anything. As the musical refrain of La Chimera so plainly spells out, ‘The tombaroli are just a drop in the ocean’. This lilting refrain ostensibly ripples out to a sentiment expressed in Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia, a film also defined by its ruined locations, an oceanic refrain, and a desperate waiting for god. Similar to the themes expressed across La Chimera, Nostalghia follows a Russian poet in Italy who longs for some irrecoverable notion, though his is of a national homeland. In his time there, he meets a reclusive mystic, Domenico, who’s known for trying to cross the baths of the town with a lit candle in his fruitless attempt to save the world. In one of their conversations, Domenico remarks: ‘When you add a drop of water to a drop of water, it just makes a bigger drop.’. Where the poet spends his time begging for god (“Lord, do you see how he’s asking?”), Domenico insists that there is no separation; all things are.

In this way, the tombaroli, Arthur, Domenico, and the poet, are all placed on the same mystic continuum, whether that’s evident to them or not. Despite the ultimately disappointing outcome in La Chima – specifically, the museum auction scene which serves as a vulgar interruption to the film’s otherwise otherworldly atmosphere – there arises here a sense of unity that’s arrived at through the conviction in desperately trying to save, and to keep. Even if the tombaroli are but a mere drop in the ocean, they’d still be part of the ocean. In Nostalghia, this dizzying unity is embodied by its wordless 12-minute final sequence, as the poet takes the baton from the mystic. Instructed to carry a candle across the drained baths in the middle of town, he grows increasingly overwhelmed by the sanctity of the act, taking pained half steps at a time. Every time the flame is extinguished, you can see something go out of him, until there’s only the flame and the movement forward. He leaves himself alive just long enough to make the offering, his last act is to shield the candlelight before he crumples, dead. The flame goes on, and the attempt is all.

For me, the intensity of that scene is mirrored in the tombaroli’s discovery of an untouched shrine. It’s the wholeness they’ve been pursuing all this time, whether they know it or not, but Arthur’s the only one who pauses long enough to really cast this look of what can only be described as awe, or the kind of love that topples you entirely. It’s a strange moment of calcified recognition that makes everything that came before it look pale and uncertain, like nothing was real until that very second. Arthur holds up the candle to the goddess’ face so gently, with such trepidation, just enough to see she looks just like Beniamina and then it’s oh god, and hello, and i’ve been looking for you everywhere.

Unfortunately, the nature of their work already means this cannot last, and so all is ruptured by Arthur having to watch his friends and companions turn love to ruin in real time, as they behead the statue to sell for profit. Watching something even death could not touch turn to dust at the hands of man is arguably one of the most frightening parts of the whole film. It’s the seepage of those capitalist instincts, what might so crassly be dubbed ‘the real world’, or ‘material reality’, all of it stomping in and trampling on the delicate unknown which couldn’t ever be born. In one fell swoop, what was a shrine is now a grave. As Arthur’s life continues in the world beyond, it’s this moment of horror which informs every decision he makes after. Namely, his eventual choice to throw the statue’s head into the water, whispering to it ‘You’re not meant for human eyes’ – a reiteration of the quiet scolding he received from Beniamina’s mother’s housekeeper, Italia – and knowing some things are meant only for the eyes of souls. Or, his leaving Italia when the promise of real love was offered to him in the possibility of making life again surrounded by a civilisation of women, who could help him live what he could only have previously experienced through death, as the Etruscans did. The pull of mysticism, of the unknown, is too great. No human life can bear it.

i guess the reason this movie has burrowed inside me the way it has is that i believe its fundamental question to be: how many opportunities do we get, really, to feel ourselves brush up against the sacred? Once in a lifetime already feels like too much, and any less is just cruel. When i wait for god, i want to be in that state for always. i know that i, for instance, felt it once when i played Morton Feldman’s Rothko Chapel in the quiet grey of an early morning before the world came crashing in. Just listening to that eerie, depthless sound, i’d feel like i was brushing against something, like time or god or whatever you want to call that great, gnawing unknowable. Just that i wasn’t alone.

It's due to this quality, the unbearable, that the final scene of the film feels as if time itself has stopped, or is out of joint entirely. In the gentle blue light of a day not yet formed, Arthur walks to his last grave, having agreed to assist a different group of tombaroli. There, the birds watch him silently, statuesque. A man holds out medallions shaped like the sun tattooed on Beniamina’s shoulder. When the mouth of the grave eventually yawns, there is nothing else to be done than for Arthur to step in and be swallowed by what he’s been pursuing all this time, as the grave’s entrance caves in behind him. Darkness covers everything, and it feels like the “depthless”1 plunge into stopped time that a visitor to the Rothko Chapel in Houston once described upon seeing its collection of imposing black paintings. i want to end on Rothko because, like La Chimera, there’s an “open grave theory” that’s been attributed to Rothko’s body of work, particularly his darker paintings, as his friend Al Jensen once suggested that it seemed “graves were locked into his work”2. All these terrible mouths into the unknown, who seem to stop time as soon as you look at them, and the unbearable rush of returning to the world in the aftermath. Rothko once said that he wanted his chapel to ‘achieve the same atmosphere that Michelangelo generated in his Laurentian Library in S. Lorenzo, Florence, which, according to Rothko, "makes the viewer feel that they are trapped in a room where all the doors and windows are bricked up, so that all they can do is to butt their heads forever against the wall."’.3

But La Chimera feels diametrically opposed to Rothko’s grave visions. Where Rothko chooses to cave in, to wall himself up alive, La Chimera insists on the grave as an opening, where what has been lost can hope to be found and loved once again. In the grave, Arthur sees the red string he’s been tugging on throughout the film, the same red string which curls around his ankle and keeps him suspended between grief and love. Finally reaching forward to action, he tugs and tugs, knowing all the while it will break, and this too will end. Just as the string snaps, the camera finds itself above ground again, framing Beniamina’s arms as she looks down at the now-useless remnant of lost love. Just when it seems time and the ground will divide them forever, Arthur’s hand reaches into the frame, getting hold of her. There’s a moment of stillness before their ecstatic embrace, which finally brings to a close the desires of Arthur’s mysticism, having finally understood that life and death are already of each other, and that it’s only through the hope afforded by believing in this lack of separation that the necessary sacrifice can be borne.

Pictures and Tears: A History of People Who Have Cried in Front of Paintings, by James Elkins, p. 111.

Pictures and Tears: A History of People Who Have Cried in Front of Paintings, by James Elkins, p. 10.

Nothingness Made Visible: The Case of Rothko's Paintings by Natalie Kosoi in Art Journal, Vol. 64, No. 2 (Summer, 2005), pp. 20-31.