Dean Winchester has come unstuck in time. there’s a moron in the White House. the growing consensus is that women are allowed to be either ‘tradwives’ or ‘girlbosses’. Dad’s on a hunting trip, and he hasn’t been home in a few days. low-rise jeans are in fashion. Eric Kripke is currently making a television show starring Jensen Ackles, Jared Padalecki, Misha Collins, and Jeffrey Dean Morgan. saving people, hunting things; the family business.

with this ‘new’ ‘era’ of ‘culture’ in which we’re being force-fed the puked-up chunks of pop culture past, the CW’s Supernatural has somehow already birthed its own mutilated reboot. The Winchesters aired on the CW for exactly one (1) season, from October 2022 to March 2023, and was watched by a total of maybe 5 people. we don’t have time to get into all of Jensen Ackles’ neuroses which resulted in rebooting Supernatural a mere 2 years after the disastrous conclusion to its 15-year run, but if everyone’s doing nostalgia bait, i’d like to say my piece. the difference being i’m doing this for fun and no profit, so i hope you’ll oblige me.

before we get into it, i do want to say why this show has lodged itself into my consciousness, and that of so many other people. obviously i won’t be able to cover everything, given there’s 20 years of posts about it and i will have missed things. but, to the best of my knowledge, there isn’t an archive that’s structured this way, and because the rise of Supernatural was simultaneous with the rise of social media (2006-2008), a lot of these things were recorded by tweets transcribing things from conventions, or interactions between CEOs, writers, directors, actors, and fans. this isn’t how people consume or engage with TV anymore (see: the decline of longform TV)1, but it seems a pity to lose all of this. not because it’s fantastic in any sort of metric way – Supernatural is far from being high quality television – but because it was a kind of enjoyment that generated a high degree of dedication and collective commitment, and it carried on at least a good 2 years after the show ended. as silly as it sounds, this show was important to me and a lot of other people once, and i’d like to remember it.

anyway! here are my parameters:

unusually strong 2000s tv fan culture: most of my tv consumption comes from this period, and while some of these shows have mostly passed the test of time, Supernatural’s longevity is in its fan culture. i haven’t encountered a single other show where fans display this much awareness of almost every single writer that worked across all 327 episodes, or refer to seasons by the era of showrunner e.g ‘The Gamble Era’. at the height of my hysteria, i had a spreadsheet which listed the writers of my favourite episodes and the character and thematic decisions they made. to some extent, i think this rationalising behaviour is because the show can be extremely inconsistent in its stance on big issues like good and evil/possession, which can flip-flop from episode to episode. this is also why i’ve chosen to do this in an anthology format, because i think it’s genuinely impossible to make any sort of cohesive, overarching argument about this show that does it any justice, and the academic articles i’ve read about it either omit the last few seasons or – pardon my language – are too far up its ass to make a good critical argument. on the other hand, i would be remiss if i didn’t admit it initially had something to do with Jensen Ackles and Jared Padalecki having perfectly contrasted pretty faces, but was carried forth by the queerbait of all time greatest to ever do it.

meta elements: while shows like Seinfeld did briefly incorporate meta elements, i think Supernatural’s use of meta was unique because it didn’t appear ex nihilo. instead, writers and showrunners knew about the fan responses, and would make certain decisions on the show in retaliation, like flat-out incorporating caricatures of fans (see: Becky Rosen, or this S5 episode set at a fan convention). all of this was then tied into the Big Meta Plot of the show, which carried on throughout all 15 seasons, and at points became an outlet for - alleged(?) - infighting in the writers room during season 15 when an agreement couldn’t be reached on how the show should end2, particularly with regards to the Destiel plotline/not-plotline/subtext/who can (n)ever be sure.

so in conclusion:

the first episode of Supernatural aired on the now-defunct WB Network on the 13th of September 2005, the day after my 6th birthday, making it a fellow Virgo. the episode drew about 5.69 million viewers3, and the show continued to average about 4.5 million viewers for each episode of seasons 1 and 2 (for context, the series finale of Succession drew 2.9 million viewers). all things considered, i think it’s fair to say that with the numbers, and having asked around, most people have at least seen the pilot of the show – whether or not they stuck around to see the rest of it. despite how the rest of the show panned out, i maintain that the pilot is a perfect distillation of Supernatural’s themes and trajectory, locating the (nuclear, american) family home as a void of terror, not safe4 inside or out. my friend R even pointed out that in one of the very first shots of the show, the Winchester family home is shot as if to have yellow eyes, the same colour as those of the demon who would be responsible for tearing their lives apart. if you haven’t seen it, i highly encourage you to pause your reading and watch the episode, because i do think it is one of the most spectacularly contained pilots ever made.

in line with its monster-of-the-week premise, familial and national mythologies are central to the thematic constructions of the show. the pilot, for instance, begins with the demise of wife and mother Mary Winchester at the hands of a demon. in the light of the blaze which takes both Mary and their home, John Winchester and his sons, Dean and Sam, are plunged into a life where “nightmares are real” (1x18) and darkness lurks around every corner. the post-9/11 context is impossible to ignore here, especially considering the multiple references to John Winchester’s militaristic upbringing of both his sons (1x09), and the isolation, paranoia, and constant vigilance he encouraged. given that horror as a genre is typically about surfacing subconscious fears– of the nation, in this case – it’s not too much of a stretch to say that Supernatural is picking up on horror’s traditional concern with encroachment. this fear, when coupled with the procedural-mystery format5 of the show, gives rise to a version of America where its own citizens must take up arms to fight against an unseen legion of darkness. one of the most striking episodes in which this fear is literalised6 is 1x04 Phantom Traveller, where the demon enters the bodies of affected airline passengers in the form of a sinister black cloud forcing its way into their orifices. though that particular association might be less potent now, you can imagine that audiences seeing it in 2005 would’ve felt it hit quite close to home, and sympathised with Dean’s fear of flying7.

“hunting”, as its referred to in the show, then becomes a way to maintain a moral order that reinforces a dichotomy of good and evil, and offers a seemingly simple, straightforward reaction to the destruction of the family unit. following this, the plot of season 1 is also straightforward in its agenda: two brothers, Dean and Sam, are faced with the mystery of “Dad’s on a hunting trip, and he hasn’t been home in a few days” (1x01). cue a 22-episode season with a clear goal, to find dad and kill as many monsters as possible on the way there. interestingly — or at least, it’s interesting to me — in the first 3 seasons, the idea that there might be a force of ‘good’ against the endless sequence of monsters that they fight is repeatedly shot down. there’s more nuance to it in the second season, but the first is an endless sequence of exorcisms and banishment, with god and his angels nowhere to be seen. in a similar vein, season 1’s lack of complexity also means that monstrosity has not found its way into the brothers just yet.

hunters, as a result, can be seen as exterminators. resigned to the margins of a society where there is only evil around every corner, the most they can do is perform the thankless task of enforcement against it, again and again. this, at best, is complicated when they’re faced with the human host of a demon (the character Meg, in this season), but while there is some discussion about the sanctity of human life and an acknowledgement of its presence in the possessed body, ultimately the need to exterminate evil snuffs out a human life too (1x22). this becomes less and less of a problem as the series goes on, which i find disappointing, and still a bit disconcerting as killing seems to become increasingly righteous.

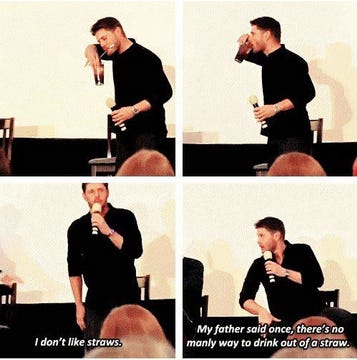

this repetition is also what helps to build the mythology of the show, which turns things as familiar as gender and genre into spaces for doubt and transfiguration. while it’s become kind of a joke in fandom spaces that this is the tv show where men drive around in cars, shoot ghosts with guns, don’t talk about their feelings, and listen to a lot of classic rock, it’s not entirely wrong. this diagnosis is both accurate and comical in recognising that repetition sets up familiar pillars for the show, but the frequency at which they’re repeated also creates doubt. take, for example, the way Supernatural handles and reinforces masculinity so self-consciously that it comes off more as a performance than anything ‘real’ or comfortable. you can probably imagine that hunting and its subconscious motivations re: protection tend to lean into masculine associations, but the show consistently draws its audiences attention to the characters’ performance of masculinity (e.g through diet, where Dean eats meat to reinforce his manliness and emasculates Sam for choosing to eat “rabbit food”, and the emotional constipation of “no chick-flick moments” right from 1x01).

put together, this suggests an anxiety where Supernatural wants its viewers so badly to believe its fiction. an instance i will never stop finding funny is that in the first season, people noticed that Sam and Dean carried umbrellas once, but spent the rest of the season walking around in the rain. when asked about this in 2022 (the show had already been over for 2 years!), Eric Kripke tweeted: ‘To be clear, I use an umbrella. So should you. It’s just that fictional cowboy demon hunters look cooler without one.’ another time, his response was, “Kim Manners directed X-Files, where they often had umbrellas, so figured it was fine. I called him, said 'the boys aren't scared of demons, but they're scared of rain?' From that point forward, a hard rule: no umbrellas.” it’s this insane obsession with performing masculinity that results in something as trivial as an umbrella signifying a lack of fear and the presence of coolness. effectively, umbrellas must be removed8 from the scene if the illusion is to be held up, even though their removal only furthers the sense that you’re watching two men strut around in their damp boy drag.

as season 1 progresses, it becomes clear that these performative ideals of masculinity were enforced by Sam and Dean’s father, John Winchester, whose absent presence hangs over the show somewhat ominously. the boys follow his doctrine faithfully, even in his absence. Dean, for example, drives his Dad’s car and dons his jacket. Sam pores over his journal to construct meaning and piece together clues as to his whereabouts. John Winchester is, for all intents and purposes, the fathergod of this show and his son’s lives, who governs every decision that both brothers make as they progress. both have an uneasy relationship with him, but while Sam “got to go to college”, Dean “had to stay home. With Dad.” (1x06)9. this gives rise to some of the central conflict of the season, emerging in exchanges like:

SAM: I don’t understand the blind faith you have in the man!

DEAN: It’s called being a good son! (1x11)

it follows that faith, in season 1, is pretty clear-cut. it’s synonymous with John Winchester who, for all intents and purposes, is god to his sons, and his journal is their bible. where he leads through vague instruction, they can only follow. the show’s mystery-based premise serves it well here, as if there was no mystery, there would be no need for faith10. or, if you’d like: “Faith is a torment. It’s like loving someone who is out there in the darkness but never appears, no matter how loudly you call”11. for Dean and Sam, this isn’t a stretch of the imagination. in 1x09 Home and 1x12 Faith respectively, each brother makes a desperate plea call to their father, who remains silent and imperceptible. it’s perhaps only natural that the tension in the brothers that pulls through the whole season is one of belief: whether to fall at the altar of John Winchester, or to stand up and walk away. like any god, John Winchester could also be cruel, and the show doesn’t shy away from this (see: 1x01, 1x06, 1x09, 1x12, 1x14, 1x22).

ultimately, what makes this show so excellent*** and hysteria-inducing is its ability to take these basic premises – like the ill-fitting relationship between father and son – and warp them to celestial proportions. we’ll get into it more as i go through the seasons, but this central conflict between creator and creation, father and son, is the path that the show insistently returns to, and that at its best, wrestles with the consequences of this gothic repetition in its narrative structure. this is especially so in the case of ‘free will’, which is still unthinkable at the end of season 1, but becomes more and more prominent as the show carries on, so much so that even its narrative becomes infected by the notion of being able to venture outside the set structure (with varying results).

season 1 ends on a cliffhanger. reunited at last, and armed with a demon-killing weapon (a gun, obviously), the three Winchesters speed towards their hunt for the demon who destroyed their family. on their way, a truck careens into the Impala, leaving them for dead. it’s a convenient way to lead into the action of the next season, but that image of the three bodies lying prone and bloody, together in their family car, has often felt to me to be the natural conclusion of the show.

if you got this far — thank you so much for reading and indulging me, i had a lot of fun doing this! i’d love to know what you thought, if you enjoyed this, or if you’ve seen the show... i do have every intention to keep this going because i like it, and my enjoyment of this show + its aftermath has everything to do with the collective effort of many crazy people, so i’d love to hear your take. there’s obviously more i wanted to include, but i think some of the other seasons do a better job of explicating certain themes and issues, so i figured i’d save them for now.

okay, that’s all. thanks to all my friends who have had to listen to me talk about this show for 4 years, you’re my heroes. see you when i see you <3

Matt Zoller Seitz, ‘TV’s Serial Drama Slump’, Variety, 2016.

i can’t spend too long on this because we will actually be here for 900 years but there’d always been this push-and-pull between the writers, showrunners and fans, plus Jensen Ackles’ many homophobia accusations (which has birthed an actual academic study), plus the pandemic and there also being evidence of an entirely different episode/scene being shot for the ending involving Castiel still being alive after confessing to Dean+dying immediately …. no one knows what happened there or why they decided to air a final episode that killed everyone off (further narrative implications, problem for later) but ….. yeah. i really don’t know what to tell you

more specifics, because i have them: while the show was briefly more popular among men than women (“achieving strong #3 ranks in the hour among men 18-34 and males 12-34”), it ultimately “kept high ratings across all 12-34 demos”. the increase in female viewers of the show came mostly during its period from 2010-2015 (though the latter shows about a 50/50 split)

or: “No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more.” (Shirley Jackson, The Haunting of Hill House)

one of the best academic articles i’ve read about Supernatural re: S1 and S2’s treatment of gender, race, and class: Latchkey Hero: Masculinity, Class and the Gothic in Eric Kripke’s Supernatural by Julia M. Wright.

the film critic Sheila O’Malley has done a ton of writing about supernatural, and it was in reading her recap of the pilot that i found out Kripke and his team wanted each episode to feel like a horror movie a week. there are definitely some that are more successful than others (1x08 bugs….1x13 route 666 i.e the racist truck episode……) but sheila’s shot-by-shot breakdowns are really fun to read to get a sense of the production, and her enthusiasm for the show is what gives her criticism its weight. here’s a masterlist of her episode recaps for s1 and s2, in case you were curious!

which leads directly into, “Why do you think I drive everywhere?”. this question not only reinforces the isolation already created by their career path, but also foregrounds Dean’s attachment to the car as a hand-me-down from his father - much like the job was - and its central position in the loneliness of the road narrative.

"To claim that this is what I am is to suggest a provisional totalisation of this “I”. But if the I can so determine itself, then that which it excludes in order to make that determination remains constitutive of the determination itself. In other words, such a statement presupposes that the “I” exceeds its determination, and even produces that very excess in and by the act which seeks to exhaust the semantic field of that “I”.” (309) — Imitation and Gender Insubordination, Judith Butler.

from this 2 minute monologue and my favourite episode of the show, but more importantly this is such a perfect Dean Character Thesis moment re: his relationship to both Sam and his father. (transcript: “You got to go to college. He had to stay home. I mean I had to stay home, with Dad. You don’t think I had dreams of my own? But Dad needed me. Where the hell were you? […] See, deep down, I’m just jealous. You’ve got friends, you could have a life. Me? I know I’m a freak, and sooner or later everybody’s gonna leave me. […] You left. Hell, I did everything Dad asked me to and he ditched me too. No explanation, nothing, just poof.”)

Conclave, 2024.

The Seventh Seal, 1957.

This was so delicious omg your analysis of just the FIRST SEASON is so incredible!!! I can’t wait to see what else you have in store

CLAPS AND CHEERS!!!! 1x06 truly thee episode of all timeeee <3